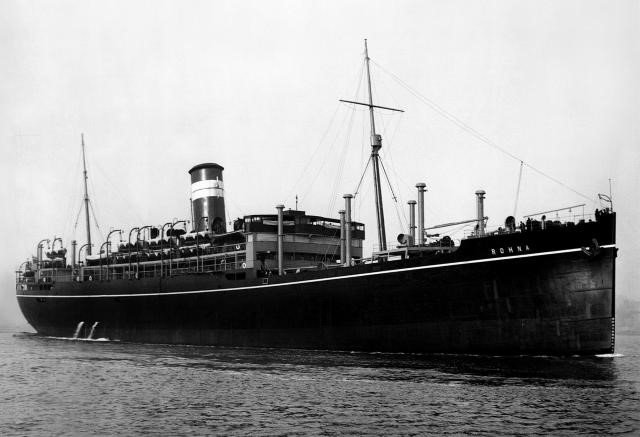

The ROHNA Disaster

The sinking of the British troopship HMT Rohna by a German guided missile in the Mediterranean on November 26, 1943, led to the greatest loss of US lives in a single incident at sea in our nation’s history. The Rohna was overloaded with 2,193 American military personnel, on their way to the China-Burma-India theater to aid in defense against invasion by Imperial Japanese troops, when she came under aerial attack. The ship was hit by an early "smart bomb"—a Henschel Hs-293 radio-controlled, rocket-boosted glide bomb, launched from a Luftwaffe bomber—that caused catastrophic damage. The ship sank in 90 minutes. Lost were 1,015 GIs, in addition to 123 of the ship’s crew. Yet the sinking of the Rohna is generally overlooked by naval historians, and most people have never even heard of the tragedy.

Honoring the Fallen: Cpl. James J. Ryan Jr.

Soon after V-J Day, men who had served with the 3rd Bomb Squadron were finally on their way back home, but members of a six-man aircrew were still listed as missing in action. Cpl. James J. Ryan Jr. had been radio-gunner in the top turret of a rocket-equipped B-25J-2, A/C #722, that went missing on May 16, 1945. It had failed to return from a bombing and strafing raid against the Japanese-held airfield at Ichang. Details of the mission and the fate of its crew were not confirmed until long after the end of hostilities.

“Flying Tigers New Emblem”

In early October of 1943, newspapers across the US announced that the 14th Air Force had officially adopted a new Flying Tigers emblem, with Maj. Gen. Claire L. Chennault's approval and endorsement. Former commander of the renowned American Volunteer Group that gained fame as the original “Flying Tigers,” as well as of the China Air Task Force that succeeded it, Chennault now served in command of the 14th Air Force. Its effectiveness soon earned it the moniker, "the Fighting Fourteenth.” Carrying on the Flying Tigers legacy under Chennault’s leadership, the 14th went on to win air superiority in China. In his memoirs, Chennault later praised the accomplishments of his air force and wrote, “It was a record of which every man who wore the Flying Tiger shoulder patch can be proud.”

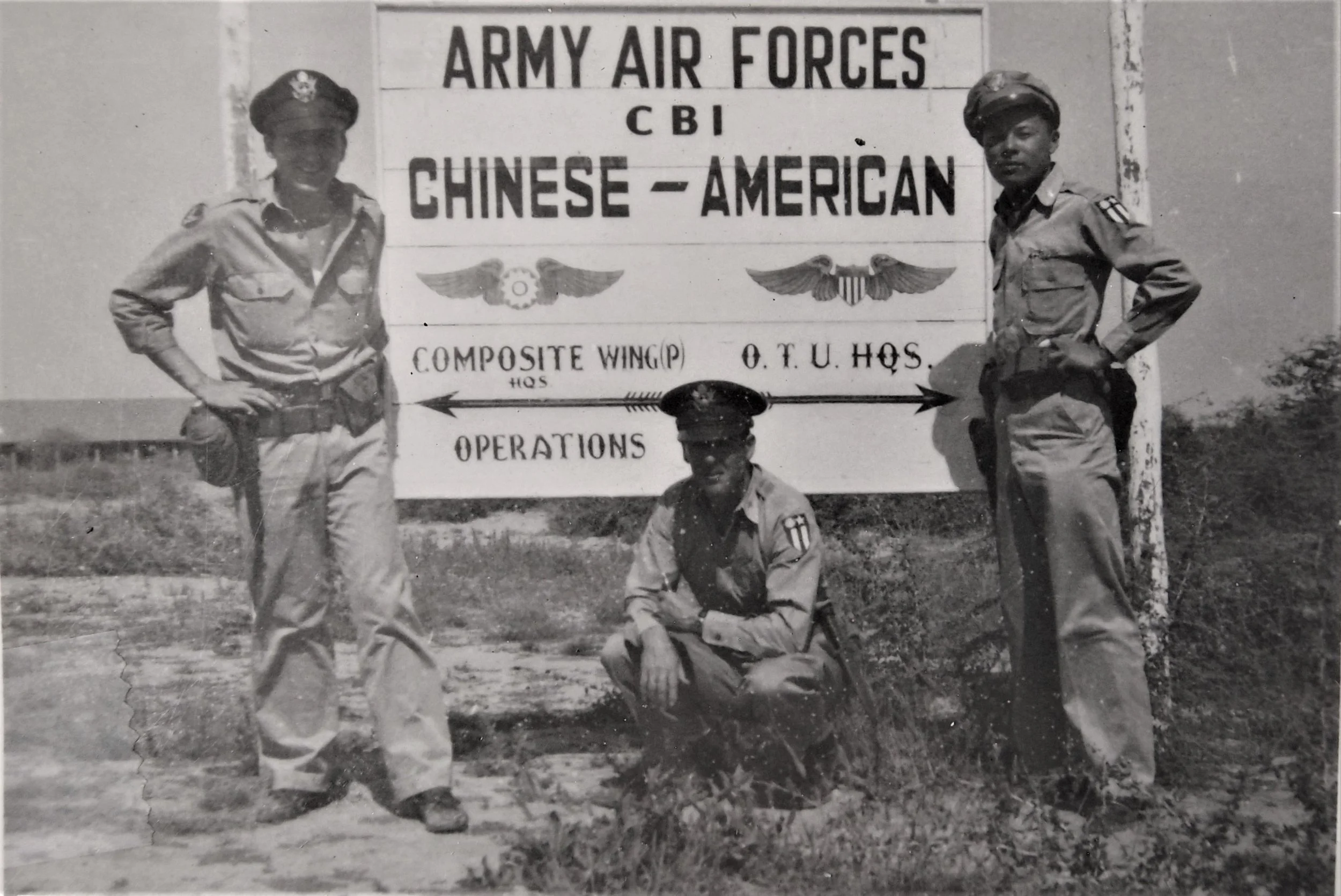

“Chennault’s Baby” Wreaks Havoc

The month of September 1945 marked the final period of existence of the CACW. “Almost two years of operations were climaxed in August by the sudden ending of the war, thus bringing about the disbanding of the Chinese-American Composite Wing,” wrote the 1st Bomb Group’s acting historical officer. Conceived by Maj. Gen. Claire Lee Chennault, famed former commander of the American Volunteer Group (AVG), the CACW took Chennault’s plan to assist the Chinese even further than his previous efforts. Their mission to paralyze the infrastructure of the Japanese War Machine and to inhibit enemy troop movements by destroying cargo caravans, troop transports, railroads, tunnels, and bridges was unquestionably successful.

Kweilin Falls to ICHIGO

B-25s assigned to the 3rd Bomb Squadron crossed “the Hump” and then made their way to Kweilin. The planes arrived at their new base on September 8, 1944—the same day the Japanese 11th Army overran Lingling, both the town and the airfield, as part of their massive Operation ICHIGO offensive. Then began their advance toward Kweilin, about 125 miles farther to the southwest. The 3rd Squadron's bombers flew only four missions before Kweilin was evacuated, all against towns in the path of the enemy drive. Final evacuation and demolition procedures began on September 14, as 3rd Squadron personnel began their move to Peishiyi by air transport, railroad, truck convoy, and the squadron’s B-25s.

Jing Baos at Kweilin

After spending the summer of 1944 bombing Japanese facilities in Burma, personnel of the Chinese-American Composite Wing’s 3rd Bomb Squadron finally began the transfer to China. Chinese and American ground crews crossed “the Hump” and moved on to Kweilin (Guilin) in late August. No Japanese planes struck in the vicinity of Kweilin during the day but "they did keep us in the foxholes night after night," according to a service publication. Barracks boys shouted the warning jing bao! ("air raid") as they ran from room to room, turning off lights and banging on wash basins to wake anyone who may have slept through the warning siren. The threat soon became more dire. On September 8, as the squadron’s B-25s were completing the move, the Japanese 11th Army overran Lingling, only 125 miles farther to the northeast. Then began their advance toward Kweilin.

Mark T. Seacrest: “Resourceful Combat Pilot”

Mid-August of 1944 found Captain Mark T. Seacrest and his binational aircrew making their way through unfamiliar territory, traveling on foot and by horseback with the aid of Chinese civilians. Seacrest had led a two-plane formation on this mission to skip-bomb a twin highway bridge near Lashio, terminus of the Burma Road's south end, but damage from concealed antiaircraft weapons forced them both down. Seacrest returned with minor injuries. One of the Chinese-American Composite Wing’s most capable and congenial pilots, he eventually completed sixty-four combat missions and had 305 combat hours to his credit, and the amount of tonnage he sank while operating in the China Sea totaled among the highest of any B-25 pilot in any theater.

Leaflets Announce Japan’s Surrender

Following an aborted mission to bomb the infamous Yellow River Bridge just north of Chenghsien, a single Chinese-American Composite Wing B-25 flew on August 12, 1945, to the Nangyang-Yochow-Siangying delta area and dropped hundreds of thousands of “informational leaflets” printed in both the Chinese and Japanese languages. They announced the joyous news that “JAPAN HAS SURRENDERED! WAR IS COMPLETELY OVER!”

Tiger Crossing and Gin March

Late July of 1944 brought about significant changes the 3rd Bomb Squadron, when they received orders to move from Moran to Dergaon. The new base was closer to the route they used to fly their B-25s over the “Low Hump” to reach Japanese targets in Burma. As they were making the move, my father, then-Sgt. James H. (“Hank”) Mills, had an encounter that he never forgot. As he was driving along a dirt road in an open weapons carrier transporting equipment, supplies, and two Chinese officers, a full-grown Bengal tiger stepped out of the bamboo thicket ahead. After discouraging the pilots from taking pot shots at the big cat, he made his way to the new base. Soon afterward, the squadron’s enlisted men were required to take “the long drill” from their tents to the flight line, twice each day, in response to the reported theft of two bottles of gin from their commanding officer’s tent. The case soon “petered out” from lack of evidence, and the squadron was declared “ready for operations.”

“Worst Thing I Ever Saw”

On June 26, 1944, notice came in through Communications, stating that the wreckage of an airplane had been spotted about twenty-five miles southeast of Moran, right at the foot of the Himalayas. A rescue crew with three jeeps, a truck, and an ambulance set out over a muddy jungle trail to the scene of the crash. Sgt. James H. (“Hank”) Mills was a member of the team. "It was the worst thing I ever saw," he recalled many years afterward. The heavy B-29 “Superfortress” bomber had broken apart and been driven into the ground. The team found no survivors, only parts of bodies. Official records still list the aircrew of “Stockett’s Rocket” as missing, although the circumstances of that crash conform to what is known about the wreckage reported by 3rd Bomb Squadron personnel.

Missionless at Moran

In mid-June 1944, personnel of the 3rd Bomb Squadron, recently relocated to Moran Field in Upper Assam, continued to prepare for joining the fight in Burma, but bad weather prevented its B-25s from flying any combat missions for more than two weeks. "It is imperative that air support be given troops surrounding entrenched Japs at Myitkyina, but insurmountable weather always intervenes," according to the official squadron history. Every day, flight crews were up early and stood by, "hoping for a clear report to warrant flying through the Himalayan Pass down to the battle area,” but every night they returned to their tents "missionless.” With morale at a low ebb, tempers were short. Several incidents that led to conflicts arose during this period, including a disagreement that led to blows and required the attention of Gen. George E. Stratemeyer, Commanding General of the Army Air Forces' India-Burma Sector.

Flying Skunks vs. Black Angels

The Chinese-American Composite Wing’s unique composition was not always readily accepted. As the 3rd Bomb Squadron prepared to enter combat in Burma, a serious conflict arose. Maj. R. L. Patterson, in command of the 83rd Bomb Squadron, 12th Bomb Group, was distrustful of the abilities of the recently-arrived and biracial 3rd Squadron. Before allowing the mixed Chinese-American crews to "tack onto" his planes for missions, he insisted that 3rd Squadron airmen fly a practice formation flight with the 83rd to demonstrate their readiness for combat. The following day, Capt. Raymond L. Hodges Jr. and "his Chinese boys, Lts. Tung and Yen" flew follow element to the 83rd Squadron's lead element. "Our boys assembled and tacked on much quicker than the 83rd, who flew an extremely wide pattern,” according to a later report. However, a mechanical failure forced the lead plane down, leaving Patterson unsatisfied, so he demanded a second practice flight. Once again, the Chinese pilots "made a wonderful showing" and Patterson called off the flight.

“Downed Baker Two Five”

May 16, 1945, began as many other days, but its events lived on in the memories of the 3rd Bomb Squadron members for many years. In the early morning hours, six B-25 crews were briefed at Liangshan on separate targets in the Ichang, Chingmen, and Shashih triangle in western Hubei Province for the purpose of hitting enemy troops and supplies on low-level bombing and strafing raids. Typical of the Chinese-American Composite Wing at this time, three aircrews were made up of all-Chinese members, and three crews were entirely Americans. Tragically, one of these bombers did not return. Aircraft #722 was hit by enemy fire over Japanese-held Ichang and crashed, burning as it went down. Five members of the crew died in the crash, and a sixth was injured as he bailed out. Captured by the enemy, he died soon afterward. The fate of these heroes was not discovered until after the war had ended.

“Just Another Day”

As the rest of the world celebrated V-E Day, it was business as usual in China’s war zone. The Chinese-American Composite Wing’s 2nd and 3rd Bomb Squadrons, with two 32nd Fighter Squadron P-51s, bombed separate targets in the vicinity of Chenghsien, Honan (Henan) Province, in Central China’s Yellow River Valley. When they received news of the German surrender soon afterward, they did not celebrate this victory but “took it just as another day.” it would be another three months before Japan admitted defeat in China. During that time, two more 3rd Squadron planes were lost, and the fate of a six-man aircrew reported as missing in action was not confirmed until after the war ended.

“Fly on Through”

By early May 1945, Allied forces in Europe were nearing victory, and the balance of power was shifting in China. The Battle of Chihkiang, in which the Chinese-American Composite Wing’s 5th Fighter Group and 3rd and 4th Bomb Squadrons played a decisive role, proved to be the turning point of the war in China. Even as the war neared an end, replacements were being sent to the China Theater. Maj. Clarence H. (“Hank”) Drake was attached as a B-25 pilot in late April and flew missions with the 3rd Bomb Squadron into June. On Drake’s first combat mission, he feared that enemy flak might bring down the plane, so he asked the pilot, “What do we do?” 1Lt. Willard G. Ilefeldt calmly replied, “Why, we just fly on through.”

Railroads and Rest Camp

After the loss of the 14th Air Force base at Laohokow, Chihkiang (now Zhijiang) became the most easterly of the bases operated by the 14th Air Force. On April 10, 1945, the Japanese initiated an offensive that claimed the full attention of the 3rd and 4th Bomb Squadrons and the 5th Fighter Group stationed at Chihkiang. So successful was the opposition against enemy targets in the Chihkiang Campaign that it proved to be the last major offensive by the Japanese in China. Even as life-or-death operations were being conducted, the daily business of the squadron went on. “All the men who have been overseas for a rather long time, or those who seem to need a little diversion and rest, are being sent to Chengtu, several at a time, to enjoy the ‘almost stateside’ atmosphere, the good ‘American’ food, and the almost white creatures of feminine pulchritude.” Five 3rd Bomb Squadron enlisted men were the next to be sent in late April.

“Smilin’ Jack” in Unflyable Condition

Beginning in mid-April 1945, about two hundred 14th Air Force fighters and bombers attacked Japanese targets in areas from southern China to the northern China plain, hitting numerous targets that included bridges, river shipping, town areas, trucks, railroad traffic, gun positions, storage areas, and general targets of opportunity. Among the attack planes were those of the Chinese-American Composite Wing. The 3rd Bomb Squadron’s A/C #714, “Smilin’ Jack,” named in honor of the squadron’s popular commander, Capt. Jack M. Hamilton, was a victim of the raid against Loyang on April 16, when a tire blew out on takeoff.

Carriers Take GIs and P-47s to CBI

USS Mission Bay (CVE-59) and USS Wake Island (CVE-65) steamed from Staten Island on February 20, 1944, loaded with Army personnel and one hundred P-47 pursuit planes bound for the China-Burma-India Theater. Accompanied by destroyer escorts USS Trumpeter, USS Straub, and USS Gustafson, the convoy formed Task Force Group 27.2. At sea for a biblical “forty days and forty nights,” according to recollections of my father, then-Cpl. James H. (“Hank”) Mills, Mission Bay went down and around the coast to South America, crossed the Atlantic, and then steamed around the coast of Africa and up to the Arabian Sea. Men aboard the carriers were assigned to cramped quarters with little to keep them occupied other than to read, play cards, and sleep. The monotony was interrupted when the carriers crossed the equator, and a traditional line-crossing ceremony got under way to commemorate the occasion. Hank remembered stops for refueling and fresh provisions at Recife, Brazil, at Cape Town, South Africa, and at Cape Diego, Madagascar, before docking at Karachi, India (now part of Pakistan) on March 29.

“Gambay Group” Hits Enemy Rails

By February 16, 1945, thirty B-25s from all four squadrons of the 1st Bomb Group—called the “Gambay Group—had converged at Hanchung for a huge raid against railroad yards at Shihkiachwang (Shijiazhuang), Hopeh (Hebei) Province, on the following day. Because their fighter escort failed to join them, the bombers separated into two elements and diverted to alternate targets in the big Yellow River bend. The first element turned south to attack railroad yards at Yunchen. The 1st Bomb Squadron’s Mitchells formed "Benton" flight, and 4th and 3rd Squadron planes made up "Charlotte." Nearly all bombs missed their targets and landed in rice paddies or villages outside the target area. The second element was slightly more effective. The 2nd Bomb Squadron and remainder of the 3rd Squadron, forming "Akron" and "Detroit" flights, turned north and attacked railroad yards, tracks, and barracks at Linfen. After a delay caused by foul weather, the four squadrons flew a successful joint mission against machine shops and rails at Taiyuan on February 21.

Chester M. (“Coondog”) Conrad

Maj. Chester M. Conrad served from March 1944 to February 1945 as commanding officer of the 3rd Bomb Squadron, 1st Bomb Group, Chinese-American Composite Wing. Known as "Chet" back home, he had picked up the sobriquet "Coondog" somewhere along the way (his radio call sign, according to my father). While previously serving in the 2nd Bomb Squadron, his aircrew was credited with shooting down a Japanese bomber. Conrad, with his 3rd Squadron, later provided air support to Chinese and American ground forces that retook Myitkyina, a Japanese stronghold used to attack Allied planes crossing the Himalayan “Hump.” He participated in many other successful missions, including a raid against storage facilities on the Hankow docks in January 1945. After his return to the US the following month, he continued to work with Chinese airmen. His military career was cut short in 1955, when then-Lt. Col. Conrad died as a result heart disease.