“Chennault’s Baby” Wreaks Havoc

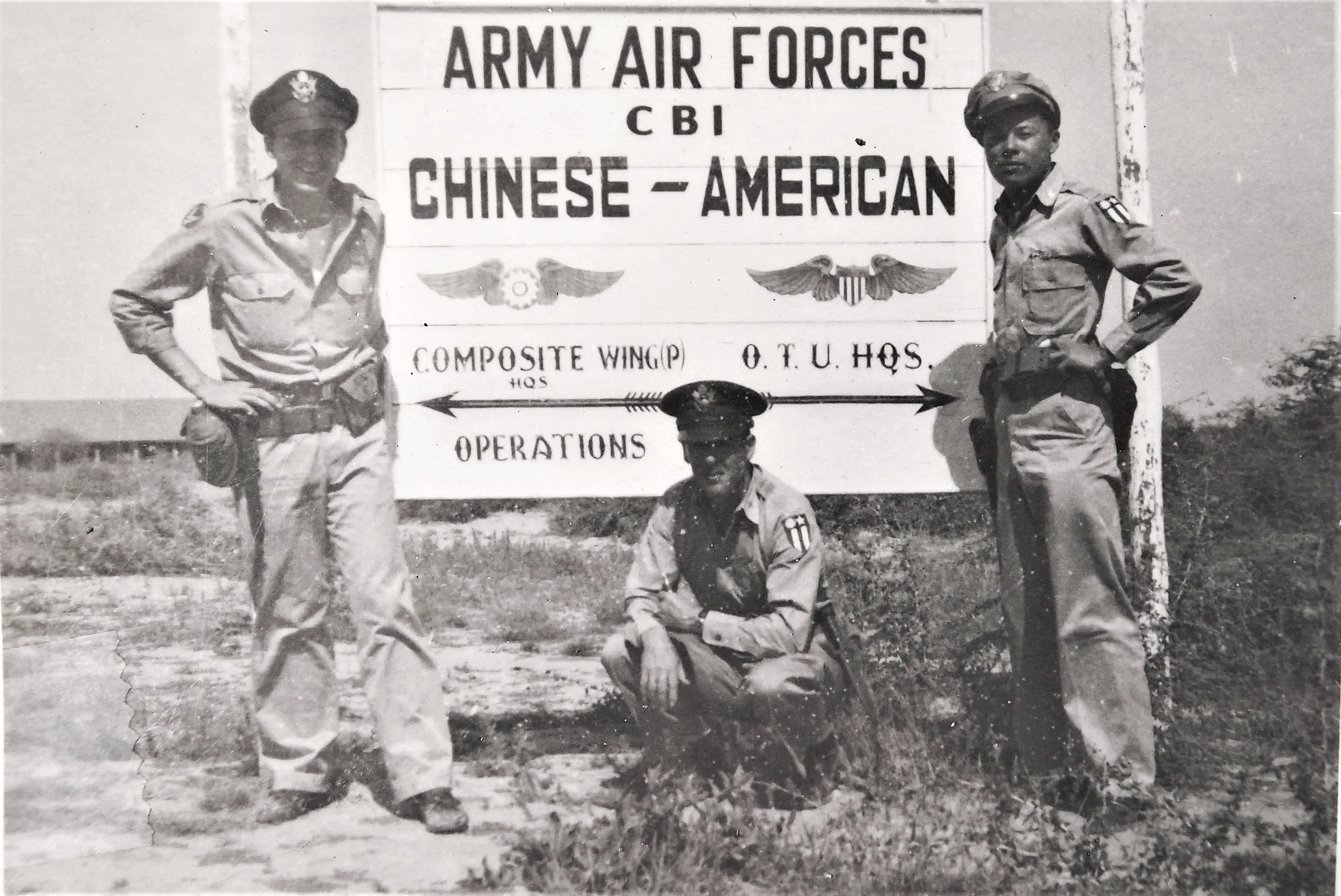

2Lt. John F. Faherty, 3rd Bomb Squadron bombardier and later armament officer (left), 2Lt. Paul L. Young, 3rd Bomb Squadron intelligence officer (right), and an unidentified officer (center) stand beside the sign marking the location of Chinese-American Composite Wing Headquarters and Operations (to the left) and the Operational Training Unit (turn right) at Malir Airdrome near Karachi, India (now part of Pakistan). All CACW bomber and fighter squadrons began their training here, with the Americans, using the latest in “know-how,” instructing their Chinese counterparts. J. H. Faherty Collection, courtesy of Dennis Faherty.

The month of September 1945 marked the final period of existence of the CACW.

“Almost two years of operations were climaxed in August by the sudden ending of the war, thus bringing about the disbanding of the Chinese-American Composite Wing. This unique unit was formed with the intention of having Americans in it who would work in close cooperation with the Chinese members of the organization and who would train them in all phases of operations,” wrote Capt. Richard T. Mallon, 1st Bomb Group adjutant (acting as historical officer). “That we were successful in welding together a striking force that wreaked havoc with Japanese supply lines, personnel, and military installations is self-evident—our record speaks for itself.”

Conceived by Maj. Gen. Claire Lee Chennault, famed former commander of the American Volunteer Group (AVG) that operated under contract to Nationalist leader Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek’s Republic of China Air Force, the CACW took Chennault’s plan to assist the Chinese even further than his previous efforts. His goal was to rehabilitate the Chinese Air Force, now decimated and debilitated by years of war against Japan’s superior forces, and to provide good will and understanding between the Chinese and Americans for the future.

It became Chennault's mission to transform the Chinese Air Force into an effective fighting force capable of fending off the invaders. Using existing CAF squadrons, the CACW trained Chinese personnel, officers and enlisted, in all phases of combat operations, as well as in maintenance and administration, according to modern American military standards.

In accordance with Chennault’s plan, one bomb squadron was trained with two fighter squadrons over a period of six weeks, with the Americans acting as mentors to the Chinese. When those squadrons completed training, they were sent to China as three more squadrons began training. This continued until a bomb group and two fighter groups, each with four squadrons, had been brought to combat readiness. Duplicate commands were established at every level. Despite vast differences in ideology, philosophy, and culture—as well as in language—the two nationalities worked effectively together, united in their determination to defeat their common enemy. *

Soon after the its activation on October 1, 1943, a Chinese war correspondent explained the concept behind this only-one-of-its-kind military organization:

The Chinese-American Composite Wing (CACW) is a force of Chinese and American airmen trained side by side, flying wing tip to tip, fighting shoulder to shoulder. Officially part of the Chinese Air Force, the command is entrusted by the Generalissimo to Major General Claire L. Chennault. The Composite Wing is equipped with modern American planes, uses battle proven American aerial tactics, [and] operates from Chinese bases with the help of Chinese intelligence. To the Americans, its value lies in the striking power it adds to the 14th Air Force. To the Chinese, it is the punch of a powerful Chinese air arm.

The CACW is General Chennault’s baby. Plans for the composite wing were suggested to Lt. Gen. H. H. Arnold, U. S. Army Air Corps Chief, by General Chennault not more than a year ago (1943). Quick action set up the Chinese-American Operations Training Unit in India, where planes and gasoline were more readily available. Group after group of Chinese and American pilots flew in from China and America. Under the dazzling blue Indian skies these men spent hundreds of hours flying B-25s and P-40s, and in studying tactics, motors and equipment. Dark blue fatigue suits of the Chinese mingle with the khaki of the American GIs on the field. The cordial atmosphere makes visitors think that two groups of men are working together, not that one is teaching and the other being taught. **

CACW bombers and fighters entered combat soon after the completion of training, initially opposing the drive that became Japan’s massive “Operation ICHIGO” in April 1944. They continued to strike the enemy through the renewed offensive in April 1945 that led to the Japanese defeat at Chihkiang (Zhijiang), in western Hunan Province. During each phase of the invasion, the CACW provided air support to the Nationalist Chinese Army, attacking Japanese ground forces and their logistical infrastructure with their B-25s, P-40s, and later P-51s.

During the last two years of the war, pilots and aircrews of the CACW battered the Japanese from one end of occupied China to the other. Their mission was to paralyze the infrastructure of the Japanese War Machine and to inhibit enemy troop movements by destroying cargo caravans, troop transports, railroads, tunnels, and bridges. Efforts by Chennault’s flyers to harass the Japanese and prevent their complete control of China were unquestionably successful. Through its two years of operations, the CACW flew more missions than the rest of the Chinese Air Force combined.

A press release published in late July (two weeks prior to the CACW’s final combat operations) praised the unit and provided statistical evidence of its successful operations.

Since November, 1943, the Chinese-American Composite Wing has flown more than 13,000 sorties, wreaking this impressive toll:

502 enemy planes destroyed, 93 probably destroyed, 309 damaged

271 locomotives destroyed, 11 probably destroyed, 283 damaged

345 railroad cars destroyed, 3 probably destroyed, 1,684 damaged

2,215 vehicles destroyed, 132 probably destroyed, 2,233 damaged

287 steamboats destroyed, 43 probably destroyed, 436 damaged

1,386 other boats destroyed, 31 probably destroyed, 5,890 damaged

46 bridges destroyed, 9 probably destroyed, 165 damaged

7 gunboats destroyed, 3 probably destroyed, 2 damaged

15,815 Jap troops killed

5,132 horses killed ***

Orders to disband the Chinese-American Composite Wing were issued on September 19. Its bomber group and two fighter groups, with all supplies, equipment, and aircraft, were transferred to the ROC Air Force Command. They went on to fight in the Chinese Civil War and later retreated to Taiwan in 1949, becoming part of the Taiwanese ROC Air Force. Today, the 1st, 3rd, and 5th Tactical Fighter Wings of the ROCAF trace their lineage to the CACW’s 1st Bomb Group and 3rd and 5th Fighter Groups.

All equipment and aircraft having been transferred to the Chinese and all personnel relieved from assignment, the Chinese-American Composite Wing ceased to exist.

After the CACW was dissolved, most of its American personnel began repositioning to be either sent back to “Uncle Sugar” by troop transport or assigned to other units in which their experience and expertise could be utilized. A small number of those were temporarily transferred to the Air Force Liaison Detachment at Chihkiang when it was activated on September 27. This team was intended to help with setting up systems of operations, maintenance, and supply so the Chinese could utilize all the American equipment being turned over to them. The liaison team was kept until the Air Mission to the CAF took over, although there was little they needed to do since duplicate commands were already in place.

Capt. Mallon, in his final report, probably best expressed the sentiments of all those departing members of the CACW:

In conclusion, let it be said that while most of the personnel who have served in the 1st Bomb Group are not exactly anxious to return to China by the first boat, they have definitely had experiences which will be good for numerous drinks in their neighborhood saloons and with which they can regale their grandchildren for years to come. The air raids, lost comrades in arms who went down fighting, rice wine, water buffalo meat with rice and vice versa, lack of mail and Post Exchange supplies, and lack of sufficient supplies with which to conduct the war will not be easily forgotten.

GOOMBAY!!

* See “Chennault’s Grand Experiment,” 10/1/2024 blog post, for more details.

** Samuel M. Chow, “Chinese-American Composite Wing,” Ex-CBI Roundup, May 1958, reprinted from China Correspondent, 1944. (Thanks to Gary Goldblatt for sharing on his “CBI ORDER OF BATTLE: Lineages and History” website.)

*** Harry Grayson, NEA Staff Correspondent, “Chinese-American Composite Wing Hits Jap Targets,” Progress-Bulletin (Pomona, CA), July 27, 1945, 2.

You can learn more about this often-overlooked outfit. Find it in The Spray and Pray Squadron: 3rd Bomb Squadron, 1st Bomb Group, Chinese-American Composite Wing in World War II.