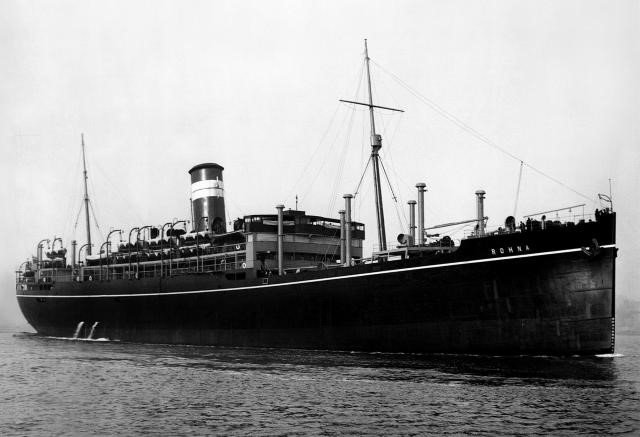

The ROHNA Disaster

The sinking of the British troopship HMT Rohna by a German guided missile in the Mediterranean on November 26, 1943, led to the greatest loss of US lives in a single incident at sea in our nation’s history. The Rohna was overloaded with 2,193 American military personnel, on their way to the China-Burma-India theater to aid in defense against invasion by Imperial Japanese troops, when she came under aerial attack. The ship was hit by an early "smart bomb"—a Henschel Hs-293 radio-controlled, rocket-boosted glide bomb, launched from a Luftwaffe bomber—that caused catastrophic damage. The ship sank in 90 minutes. Lost were 1,015 GIs, in addition to 123 of the ship’s crew. Yet the sinking of the Rohna is generally overlooked by naval historians, and most people have never even heard of the tragedy.

Carriers Take GIs and P-47s to CBI

USS Mission Bay (CVE-59) and USS Wake Island (CVE-65) steamed from Staten Island on February 20, 1944, loaded with Army personnel and one hundred P-47 pursuit planes bound for the China-Burma-India Theater. Accompanied by destroyer escorts USS Trumpeter, USS Straub, and USS Gustafson, the convoy formed Task Force Group 27.2. At sea for a biblical “forty days and forty nights,” according to recollections of my father, then-Cpl. James H. (“Hank”) Mills, Mission Bay went down and around the coast to South America, crossed the Atlantic, and then steamed around the coast of Africa and up to the Arabian Sea. Men aboard the carriers were assigned to cramped quarters with little to keep them occupied other than to read, play cards, and sleep. The monotony was interrupted when the carriers crossed the equator, and a traditional line-crossing ceremony got under way to commemorate the occasion. Hank remembered stops for refueling and fresh provisions at Recife, Brazil, at Cape Town, South Africa, and at Cape Diego, Madagascar, before docking at Karachi, India (now part of Pakistan) on March 29.

“Moonless-Night Missions”

In late 1944, it became clear to observers that Japanese forces coming from the north were moving toward a junction with troops advancing westward toward Nanning from Canton. Col. John A. Dunning, in command of the 5th Fighter Group at Chihkiang (Zhijiang), put in a request for four B-25s with crews to run missions in close conjunction with his "Flying Hatchet" fighters to resist the enemy drive. His pilots had found that daytime targets were scarce and scattered because the enemy was moving troops and supplies primarily at night, so that was when he intended to strike. Called "Task Force 34," its participants were detached from the 3rd and 4th Bomb Squadrons, and the majority of their missions were night single-plane strikes at river, rail, and road traffic in the Hsiang Valley and from Hankow to Kweilin. Many of them were accomplished without moonlight. So successful were these “moonless-night missions” that they became a specialty of Task Force 34.