The ROHNA Disaster

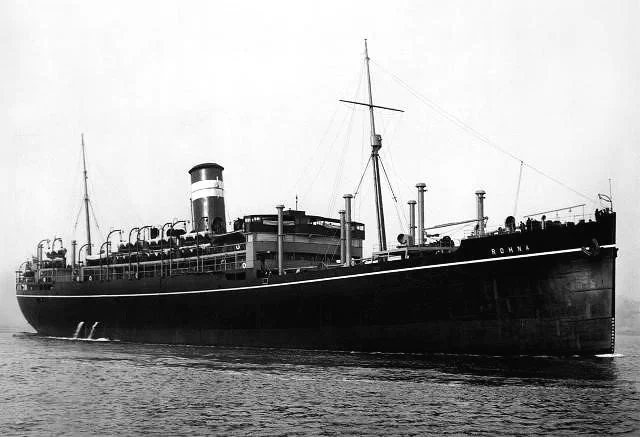

The Rohna (seen here in prewar service with the British India Steam Navigation Company), was overloaded with US troops and steaming through the Mediterranean along “Suicide Alley” when she was attacked by German Luftwaffe bombers. Hit by an early "smart bomb"—a Henschel Hs-293 radio-controlled, rocket-boosted glide bomb—the ship received catastrophic damage that led to the tragic deaths of more than a thousand of those onboard. For decades afterward, all parties involved kept details of the attack a carefully-guarded secret. Public Domain

“I know now that the most helpless feeling in the world is to stand on a ship and watch a bomb coming down and hear it whistling. All you can do is stand there, ready to jump, and hoping it doesn’t hit.”

Maj. William B. McGehee, later adjutant for the Chinese-American Composite Wing, was a witness to the greatest loss of US military personnel from enemy attack at sea in any single incident in our nation’s history. From Greenville, Alabama, he occasionally sent letters back home to the local newspaper for publication, and he included his impressions of the horrific experience, although providing few specifics, in his missive dated February 16, 1944.

“We left Africa finally and were on our way through the Mediterranean to this theater. . . . There we got our first real taste of this war when a bunch of German bombers knocked the hell out of us twice.” Although they only sank one ship out of the convoy, “it was certainly touch and go for a while.” The ship on which he was a passenger got through without damage, but “quite a few” friends with whom he had served at Eglin Field didn’t make it, he wrote. “It was a pretty rugged two days, but it could have been worse.” He concluded that “those people who said the Mediterranean was ‘an Allied lake’ at that time didn’t know what they were talking about.” *

Among the 1,157 who perished when HMT Rohna went down on November 26, 1943, off the coast of French Algeria near Bougie, were 1,015 US soldiers. This total was marginally less than the much-publicized loss of 1,177 sailors aboard USS Arizona (BB-39), that was moored and not at sea when the Japanese sank it in their attack at Pearl Harbor, while Rohna’s US casualties far exceeded the 879 who died when USS Indianapolis (CA-35) was torpedoed in the Pacific near the end of the war. Yet the sinking of the Rohna is generally overlooked by naval historians, and most people have never even heard of the tragedy.

During this period, the United States was transferring Army and Army Air Corps personnel to the China-Burma-India theater to oppose the invaders from Imperial Japan, including on a route via the Mediterranean Sea. Units were first transported aboard American troopships from the US to the Mediterranean, passing through the Strait of Gibraltar and steaming east along the coast of North Africa to the port city of Oran, French Algeria. GIs then boarded British troopships to join a “KMF” convoy (UK to the Mediterranean, Fast) that had earlier departed Great Britain. The convoys traversed the Suez Canal, passed through the Red Sea to the Arabian Sea, and finally steamed eastward to India. Personnel were then dispersed to their intended destinations, either there or sent on to Burma or China.

These British troopships were generally converted passenger liners, requisitioned as His Majesty’s Transports (HMTs). As the war escalated and greater troop capacity was required, the British transferred four smaller cargo/passenger ships operated by the British India Steam Navigation Company from the Indian Ocean. One of these was the Rohna, along with her sister ship Rajula and fleet companions Karoa and Egra.

As KMF-26 passed Oran on Thanksgiving Day, November 25, a US contingent comprising the Rohna, Rajula, Karoa, and Egra, accompanied by two destroyer escorts and two minesweepers, joined the Gibraltar-to-Suez convoy. A mechanical failure sent the Rajula back to Oran almost immediately. Positioned in “the coffin corner” (second from the leader, considered the most vulnerable location), the Rohna continued with the two-dozen-ship convoy toward Alexandria, Egypt.

By the time of her transfer to the Mediterranean the previous April, the Rohna was 17 years old and had completed 120 voyages. When the decrepit vessel arrived to collect personnel for KMF-26, it was her first time transporting US soldiers. More akin to a crowded bus than a luxury ocean liner, the Rohna was certified to carry 3,851 unberthed “deck” passengers (originally intended for poor Indian laborers seeking work elsewhere), in addition to the 414 that could be accommodated in cabins. Loaded with 2,193 military personnel and 195 crew members, she carried more than twice the number that could be quartered comfortably and safely.

With a total of 823 men, officers and enlisted, the 853rd Engineering Battalion, Aviation Corps of Engineers, made up the largest component on board. Their intended purpose was to build B-29 airfields in preparation for bombing the Japanese home islands. Other units were the 322nd Fighter Control Squadron (later sent to China and attached to the 51st Fighter Group, 69th Composite Wing, to provide communication by means of radio, air-to ground, and point-to-point), the 31st Signal Construction Battalion (later responsible for setting up signal wiring across Assam in northeast India, through Burma, and on to Kunming, China), and the 44th Portable Surgical Hospital (originally intended to provide medical care to military personnel in China but, attached to the 475th Infantry Regiment, served in Assam, India, and later northern Burma).

Other smaller components aboard the Rohna were one Army and four Army Air Forces “filler” units. Their purpose was to provide additional or replacement personnel to existing units already in operation. An undetermined number of these “fillers” were to be assigned to the Chinese-American Composite Wing for the purpose of training the Chinese to defend themselves against the Japanese. In April 1944, when personnel were attached to the CACW’s recently-formed 17th Fighter Squadron, 5th Fighter Group, they learned that they were replacements for a unit that had been lost at sea when their ship was attacked and sunk in the Mediterranean.

Lt. Col. Alexander J. Frolich, the senior officer on board, was also the commanding officer of the 853rd Engineers. In his capacity as commander of US troops, Lt. Col. Frolich took his responsibility seriously and held various drills over the two days at sea, including abandon-ship drills. Although his knowledge of proper procedures was limited by lack of experience, he was determined to ensure his men were ready for an attack or other emergency. However, they were completely unprepared for the magnitude of the catastrophe that soon befell them.

At about 1630 on the 26th, approximately 30 aircraft attacked the convoy in two major waves. They included fourteen Heinkel He-177A heavy, long-range “Greif” ("Griffin") bombers, escorted by Junkers Ju-88 aircraft, and followed by between six and nine torpedo bombers. The German planes operated out of France with the Luftwaffe's Kampfgeschwader (KG) 100th Bomb Wing. Land-based Allied fighter aircraft disrupted much of the attack, and the Rohna's own gunners contributed significantly with her anti-aircraft weapons. The convoy shot down at least two aircraft and damaged several others. **

KMF-26 avoided losses until about 1720, after the second wave hit. As dusk descended, a single He-177A-3 bomber, piloted by Maj. Hans Dochterman, launched a rocket-propelled, radio-guided Hs-293 “glide bomb.” Dochterman’s bombardier steered the Hs-293 into the Rohna’s port side at the after end of her engine room and No. 6 troop deck. Hitting about 15 inches above the water line, it caused a massive explosion. The damage resulted in raging fires and complete loss of power. The greatest loss of life in the early stages of the disaster was in the 853rd Engineers, quartered near the engine room. Of the US soldiers on board, about 300 perished almost immediately from the blast, resultant flooding, or conflagration, leaving about 1,700 soldiers to abandon ship, along with the surviving officers, crew, and several dozen British military and medical personnel. The ship began listing to starboard. Terrified men poured on deck, many of them seriously wounded. In the absence of clear communication, many made the decision to abandon ship.

The impact additionally demolished the No. 4 bulkhead, destroying six of her 22 lifeboats. It also forced out the plates of her hull, preventing any of the surviving portside boats from being lowered past them. Indian crewmen reacted as well as could be expected, according to a later report, and one group launched a lifeboat and rowed away, leaving the soldiers, who had not been trained in deployment of lifeboats, to fend for themselves. Much of the equipment was immobilized by rust and covered by layers of paint. Of the few that could be released, the davits, winches, and cables failed. Troops cut the ropes of some of the boats, causing them to plummet into the sea and sink. Only eight were successfully launched, but these boats were overloaded with troops and most were swamped or capsized.

Others attempted to use the ship’s 101 smaller life rafts, only to find that they, too, had been “welded” to the hull by layers of rust and paint. Few could be released, and most of those were tossed overboard while the ship was still making headway and disappeared empty into the darkness. By 1750, only a few rafts remained, so the desperate men took the hatch boards from the No. 3 hold and threw them overboard for flotation, too.

When it became apparent that they would have to jump into the frigid, choppy, oily water, the soldiers relied on the M1926 life belts they had been issued. These were not kapok life jackets or inflatable “Mae West” life vests, designed for long-term use in deep water. Instead, they were inflatable tubes designed to be worn around the chest, under their armpits, and intended for use in shallow water for brief periods. Since the soldiers had not received instructions in their use, many positioned the life belts around their waists, causing them to flip head-down into the sea and drown.

Meanwhile, the convoy’s undamaged ships moved in for the rescue, notably the minesweeper Pioneer, which, in a heroic effort while under attack, retrieved more than 600 survivors. Cargo ships and an escort destroyer rescued others, and within hours additional ships arrived to join the search. Many of those awaiting rescue succumbed to hypothermia, exhaustion, or as the result of their wounds before they could be saved. The rescue continued until 0215 the next day. Most of the US survivors were initially taken to a British camp at Philippeville (now Skikda). There they were warned that any communication about this event to others, or in letters back home, would result in court martial.

In the early morning hours of November 27, of the 853rd Engineering Battalion’s original 793 enlisted men, only 126 answered roll call. Lost were 10 officers and 485 enlisted men, for a loss rate of more than 60%.

One of the survivors attached to 853rd Engineers was then-Cpl. Isadore F. Hoke. Records state he departed the US for North Africa on October 2, 1943. Hoke‘s injuries consisted primarily of contusions to the right thorax, according to military hospital admission records. He was released the following month. He later stated that he was hospitalized in Constantine, Algeria, and Bizerte, Tunisia, before rejoining his unit in India. Censorship prevented his mother in Pennsylvania from receiving assurance of his survival until notification from the National Jewish Welfare Board dated January 24, 1944. He was attached to the Chinese-American Composite Wing’s 3rd Bomb Squadron soon after its activation in February 1944 and assigned duty as an armorer and later as gun turret specialist on B-25s. Hoke worked closely with my dad, then-Cpl. James H. Mills, who remembered this about Hoke: "He was the one that was on a troopship. The Germans sank it and he survived that sinking, but he was goofy in the head after that.” Although a hometown newspaper stated that he served as an aerial gunner, his name does not appear among aircrew rosters on combat missions. Like other Rohna survivors who sustained injuries, Hoke was later awarded the Purple Heart.

Cpl. Harold G. Sarver, another survivor, was briefly assigned to the 3rd Bomb Squadron at about the same time as Hoke. His hometown newspaper later stated that he suffered burns but “escaped death when the ship upon which he was traveling was struck by a torpedo in the Mediterranean and sunk.” (Since use of “glide bombs” had not been made public, they were often misidentified as “aerial rockets.”) He recovered from his injuries and was attached to the CACW’s 4th Bomb Squadron in early 1944. It is ironic that Sarver lived only about six months following his rescue from the Rohna, and his fiery death at sea closely resembled circumstances he had previously escaped. ***

On May 12, 1944, a two-plane sea sweep from Kweilin (now Guilin), in southern China, was off to the vicinity of Hong Kong. It was a joint mission, with a 1st Bomb Squadron B-25 in the lead and a 4th Bomb Squadron plane on its tail. Sarver was in position as tail gunner of the following Mitchell. Low ceiling and scattered rain limited visibility. At approximately 1300, crewmen sighted a lone boat (later identified as a Japanese gun boat) and attacked it. When the trailing plane passed over the vessel at skip-bombing height, its right wing was either shot off by enemy fire or sheared off by the mast of the gun boat. It fell into the sea in two parts, both of which “burned fiercely” for a few moments and then sank, according to the operational report. Cpl. Sarver was one of a five-man aircrew (four Americans and one Chinese) who were lost. Their remains were determined to be unrecoverable. The Americans, memorialized at the Manila American Cemetery in the Philippines, were all posthumously awarded the Purple Heart. It was Sarver’s second.

Three official accounts were submitted soon after the loss of the Rohna. The first report was from survivor and British Army Maj. James C. Lindsell, written on November 28. His note was also signed by Lt. Col. Frolich. Capt. Elmer W. Grimes of the US Army Transportation Corps, who reached Philippeville by 1530 the day after the attack, wrote the second report on November 29. The final report by Frolich was written on November 30.

All the accounts described the attack in similar ways, and they also either ignored or understated the difficulties encountered in abandoning ship. None mentions the poor condition of the lifesaving systems on board the ship. The reports were instantly classified “Secret,” and the official silence began.

One reason for secrecy may have been to avoid providing useful intelligence to the enemy, but a more likely explanation involves the weapon used. The Hs-293 was a radio-controlled, rocket-boosted glide bomb—sometimes called “Hitler’s secret weapon”—that had wreaked havoc on Allied navies through the previous summer. Commanders were concerned that their sailors and soldiers would become demoralized if they concluded the Germans had achieved a superweapon against which the Allies had few defenses.

Bodies of most of the lost were never recovered. The War Department initially informed next of kin that their soldiers were “missing,” omitting the detail that the incident involved a troopship lost at sea. Many of the families held onto hope that their soldiers would soon return or were alive as prisoners of war.

By early 1944, there were “rumblings in Congress” that families were being misled as to the status of their soldiers lost with the Rohna. In February, the US Government had acknowledged that more than 1,000 soldiers had been lost in the sinking of an unnamed troopship in European waters, but it hinted that a submarine was responsible. The Adjutant General’s Office concluded that a proper investigation was warranted, including interviews with survivors. This was not a simple task. The survivors by that point were scattered across India, Burma, and China. In the end, 85 were tracked down. Accounts of the pandemonium during the process of abandoning ship survive by virtue of the detailed interviews completed through the following months and additional firsthand accounts collected after the war. They consistently described scenes of chaos and desperation.

By June 1945, the US War Department had publicly identified the ship as the Rohna and released accurate casualty figures. The cause of the sinking was identified as German bombers but did not mention that a guided bomb was used. The Army finally notified the families of those killed that their status had been changed from “Missing in Action” to “Killed in Action.”

Although a few US newspapers leaked information about the use of a "glider bomb" soon afterward, critical details about the attack, and the subsequent investigations, were kept classified for decades. It was not until 1967, after the passing of the Freedom of Information Act, that the US Government officially released the remaining details of the incident, specifically that a radio-controlled glide bomb had been used.

* “Interesting Letter Tells of Service in China and India,” Greenville Advocate (Greenville, AL), March 2, 1944, 3.

** “Learn About the Rohna,” The Rohna Survivors Memorial Association, 2013. https://rohnasurvivors.org/

(In my earlier research for my book, details I discovered stated that Dornier Do-217s were responsible for sinking the Rohna, but sources such as this have updated information based upon more recent findings.)

*** “Cpl. Harold Sarver Is Killed in Action,” The Post-Star (Glen Falls, New York), June 5, 1944, 2.

**** Martin J. Bollinger, “The Rohna Disaster,” Naval History, US Naval Institute, December 2024. https://www.usni.org/magazines/naval-history/2024/december/rohna-disaster

Other sources used for providing details to this account:

Samuel J. Cox, Director NHHC, “Forgotten Valor: USS Pioneer (AM-105) and the sinking of HMT Rohna, the Worst Loss of U.S. Life at Sea, 26 November 1943,” H-Gram 022, Attachment 2, Naval History and Heritage Command, May 8, 2019. https://www.history.navy.mil/about-us/leadership/director/directors-corner/h-grams/h-gram-022/h-022-2.html

“The Sinking of the HMT Rohna,” The National WWII Museum, New Orleans, LA. This article was contributed by The Rohna Survivors Memorial Association. https://www.nationalww2museum.org/war/articles/sinking-hmt-rohna

Caitlin McHugh, “Unraveling the Secret Behind the HMT Rohna,” Ezra’s Archives, Cornell University, Department of History (no date), 55-67. https://ecommons.cornell.edu/server/api/core/bitstreams/ e72cd9c8-d14d-41b0-a1c6-5797fc2f91f5/content

You can find this story, and other riveting accounts of courage in the face of disaster, in The Spray and Pray Squadron: 3rd Bomb Squadron, 1st Bomb Group, Chinese-American Composite Wing in World War II.